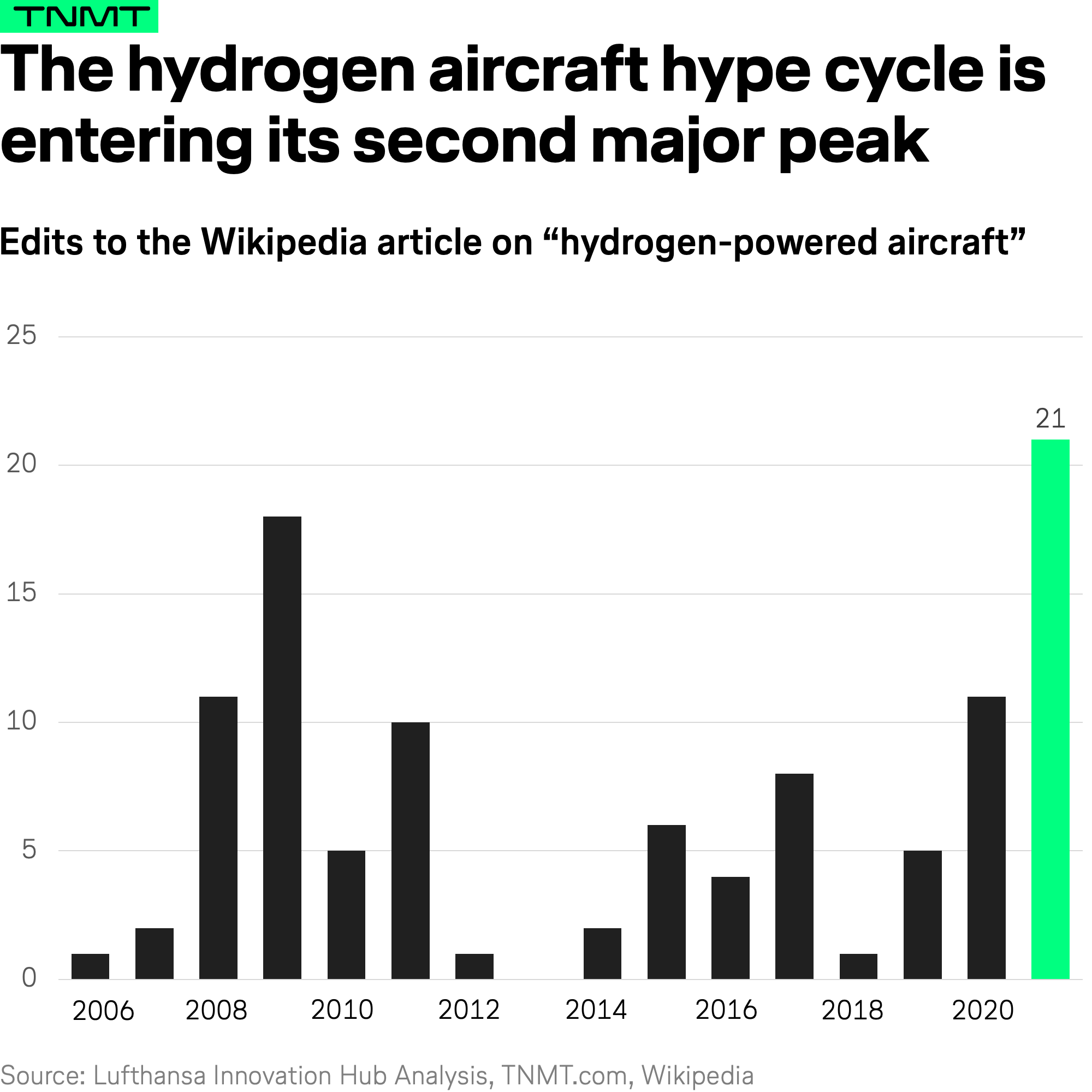

Recently, we tested the power of Wikipedia in predicting hype cycles in aviation.

Based on the number of edits made to the Wikipedia page on aviation biofuel, a.k.a. Sustainable Aviation Fuel, we identified 2020 as the “Year of SAF.” To learn more, check out our analysis here.

How about hydrogen flying?

To better understand Wikipedia as a trend indicator, we extended our approach. We looked at another Green Aero Technology that could affect the future of sustainable aviation—hydrogen.

Here’s how we went about it:

- We checked out the Wikipedia page on hydrogen-powered aircraft and scraped through the number of edits made to the article on an annual basis.

- We only included edits made of at least 80 characters, given that shorter edits generally only referred to typos or minor corrections with little influence on the actual content of the article.

- As well, we excluded all edits possibly generated by bots.

Next, we plotted the edits on a chart, as you can see below:

What can we learn from this?

There are a couple of interesting takeaways from this chart.

First, the Wikipedia page for hydrogen-flying aircraft was created in 2006. This demonstrates that the subject has long been discussed and researched in the aviation industry. By contrast, the Wikipedia page for air taxis and evtol is just three-years-old.

With this in mind, it’s safe to say that hydrogen itself is not necessarily a “new” technology.

- Rather, the first experimental aircraft to use hydrogen as fuel can be traced back to 1988.

- Airbus, on the other hand, has been involved in hydrogen-related research from as early as 2000, including a major 2002 study that found that a so-called hydrogen-powered Cryoplane would not be viable.

- A couple of years later, the aircraft manufacturer returned to the idea before inevitably ditching it again in 2010.

When looking at the trend line of Wikipedia edits, shifting perspectives over the effectiveness of hydrogen as a sustainable fuel option are highlighted.

Between 2006 and 2012, we found several fluctuations with a major spike taking place in 2009. Interestingly, this phenomenon aligns with more frequent press announcements made by Airbus and other aviation companies that year.

Hydrogen < SAF

Another interesting insight is that the average number of edits per year for hydrogen-powered aircraft is far lower than that of Sustainable Aviation Fuel. To find out more, check out our first Wikipedia analysis.

The aforementioned insight could mean the aviation industry has higher expectations for the impacts of aviation biofuel than hydrogen. This would make sense given that SAF is a ready-to-use solution for airlines to substitute conventional jet fuel, whereas the commercial application of hydrogen appears to be at least a decade away.

The year-long plateau until COVID

Following the 2009 spike, editing activity slowed down with minor fluctuations in the several years to come.

In 2017, there was a slight uptake in edits. However, these edits seem to neither correlate with major news nor events in the industry at that time, as far as we can tell.

The second hype phase began in 2019

Since 2019, however, we see a clear uptake in edits.

This appears to be in line with hydrogen gaining steam as a public narrative again, alongside airline investments in Green Aero Tech startups peaking, as we recently explored.

For instance, Universal Hydrogen—a leading startup developing modular hydrogen capsules—managed to raise $62 million USD in early-stage VC funding from a group of investors, including Airbus and JetBlue.

Over the past two to three years, the buzz surrounding hydrogen has been revitalized. Once more, Airbus geared up for a hydrogen jet, this time one that is closer to reality, according to the Financial Times.

On top of this, increasing pressures from governments and climate activists pushing for an alternative to conventional jet fuel have added further steam to the public narrative.

Long story short

2021 turned out to be a record year for the number of edits to the hydrogen-aircraft Wikipedia page. We believe this trend correlates with the growing attention to the overall topic of hydrogen that occurred within the industry last year.

Undoubtedly, altogether this does not make a hydrogen-aircraft future more realistic.

The discussions swirling around the technology haven’t changed much over the years.

The majority of industry experts agree that the potential benefits of hydrogen are quite clear.

Liquid hydrogen, for example, could provide roughly 2.5 times more energy per kilogram and produce up to 90% fewer nitrogen oxides than kerosene fuel, which is a big advantage compared to today’s status quo.

Even more promising is the case of fuel-cell propulsion.

As the Sustainable Aero Lab from Hamburg nicely summarizes:

- Unlike batteries, which need to be recharged, fuel cells continue to generate electricity as long as a fuel source (hydrogen) is provided, enabling faster turnaround times.

- Individual fuel cells can be “stacked” to form larger systems that can produce more power, thereby allowing scalability. And, since there are no moving parts, fuel cells are silent and reliable.

- Last but not least, hydrogen is superior to conventional fuel in terms of power density by unit weight. This is relevant for weight-critical flying, given that it offers a maximum takeoff weight advantage over all other energy storage alternatives.

The challenges remain

Despite optimistic statements and outlooks by companies, such as Airbus in 2021, major technological challenges remain:

- Hydrogen has a lower volumetric density, which means it requires four to five times the volume of conventional fuel to carry the same onboard energy. Massive tanks are required for this.

- Additionally, hydrogen must be cooled down to -253 ºC to be available in the liquid form. There would be additional costs associated with the chilling of hydrogen.

In summary, while hydrogen appears to be the sacred path forward, there are roadblocks along the way. The solutions offering the greatest opportunities to reduce emissions require novel engine or aircraft architectures and/or novel electrical systems.

Only time will tell how the future of hydrogen will play out.

According to IATA, it will be used commercially by 2030 in the best-case scenario.

Until then, we expect a lot of new edits to the Wikipedia page