By plane from Hamburg to Frankfurt?

“Unacceptable, shame on you, climate sinners!”

These are just some of the words you would have heard from participants of the “Fridays for Future” movement in 2019. Twitter hashtags like #flyingshame or #flugzeugfasten helped propel the airplane to become the ultimate scapegoat for climate change, with extreme calls to ban domestic flights altogether.

But how serious is the impact of domestic flights on climate change? Let’s take a look at the facts for Germany.

The environmental impact of domestic flights

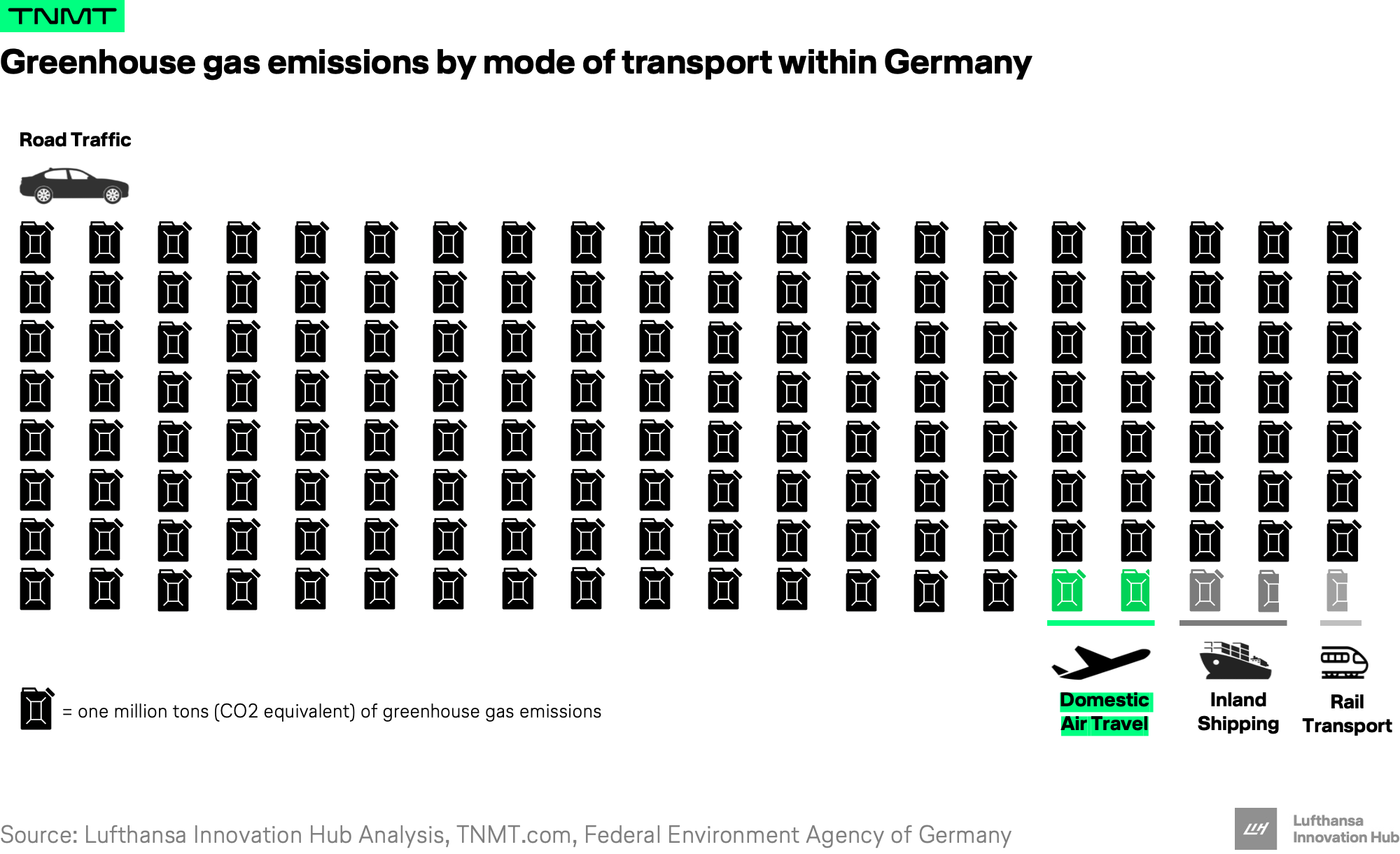

In 2019, total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in Germany across all sectors totaled 805 million metric tons of CO2 equivalents – a unit of measurement scientists use to offset carbon dioxide emissions against other greenhouse gases.

The transport sector alone, which totalled 163 million tons, accounted for 20.3% of total emissions. And domestic flights? They represented a mere 0.24% or 1.955 million tons. By contrast, motorized individual transport (mainly cars and motorcycles) was responsible for 159 million tons of GHG, or 19.8% of total emissions. Rail transport had the lowest impact among the different transport modes with only 776,000 tons, representing 0.10% of total emissions.

Here are the visualized figures for a more intuitive comparison:

The takeaway: The effect that a reduction in road traffic volume would have on GHG emissions would be many times greater than prohibiting short-haul flights within Germany. Stopping domestic flights alone would only make a dent on current emission levels.

Road traffic is really to blame

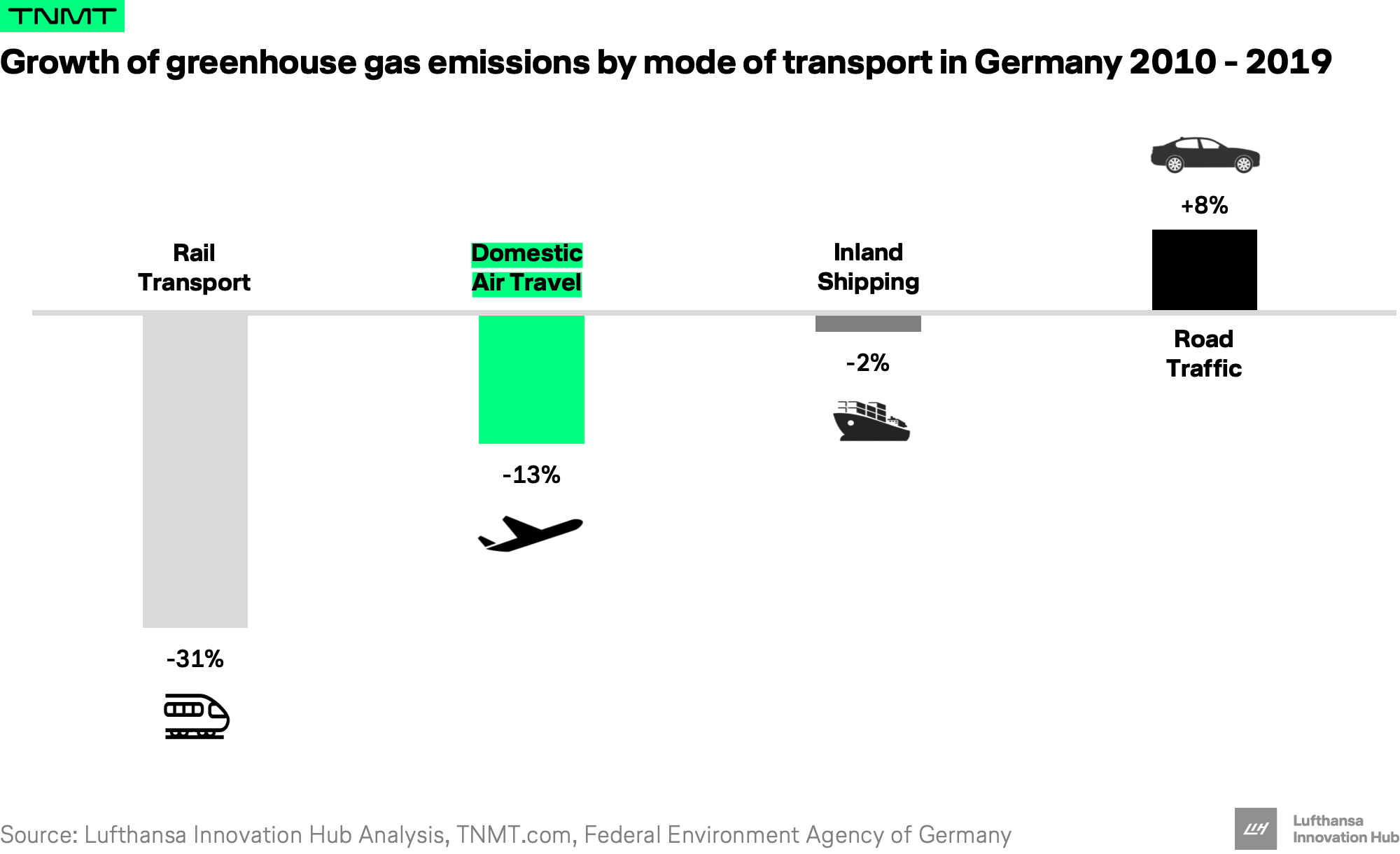

Let’s take a look at how GHG emissions developed over the last ten years for a better understanding of which of the four transport modes improved the most from an efficiency perspective.

It turns out, road traffic is the only major transport mode showing an increased growth of emissions within the last ten years, driven by a higher density of cars in Germany (up 12% in 2019 from an average of 509 cars per 1,000 inhabitants back in 2010).

All other segments – rail (-31%), air travel (-13%), and inland shipping (-2%) – were able to decrease GHG emissions over time.

Air travel’s reduction in carbon emissions is especially astonishing, given the fact that air passenger numbers in Germany grew by a phenomenal +36% over the same time frame. Fuel-efficient aircraft, more efficient use of airspace through new landing procedures, smaller aircraft sizes, and better planning of optimal flight routes enabled airlines to grow their business while reducing their environmental impact.

Disclaimer: Of course, when comparing different transport modes based on their CO2 output, it’s important to also break down the data on a per-capita basis. Credible data is really hard to find and a clear apples-to-apples comparison is almost impossible. Nevertheless, here is our best-educated research approach. We looked at dozens of calculations from various trustworthy sources. By the way, Lufthansa’s short-haul flights (<800km) emitted 148.6 grams per passenger kilometer in 2019, which is considerably lower than the average gasoline or diesel vehicles.

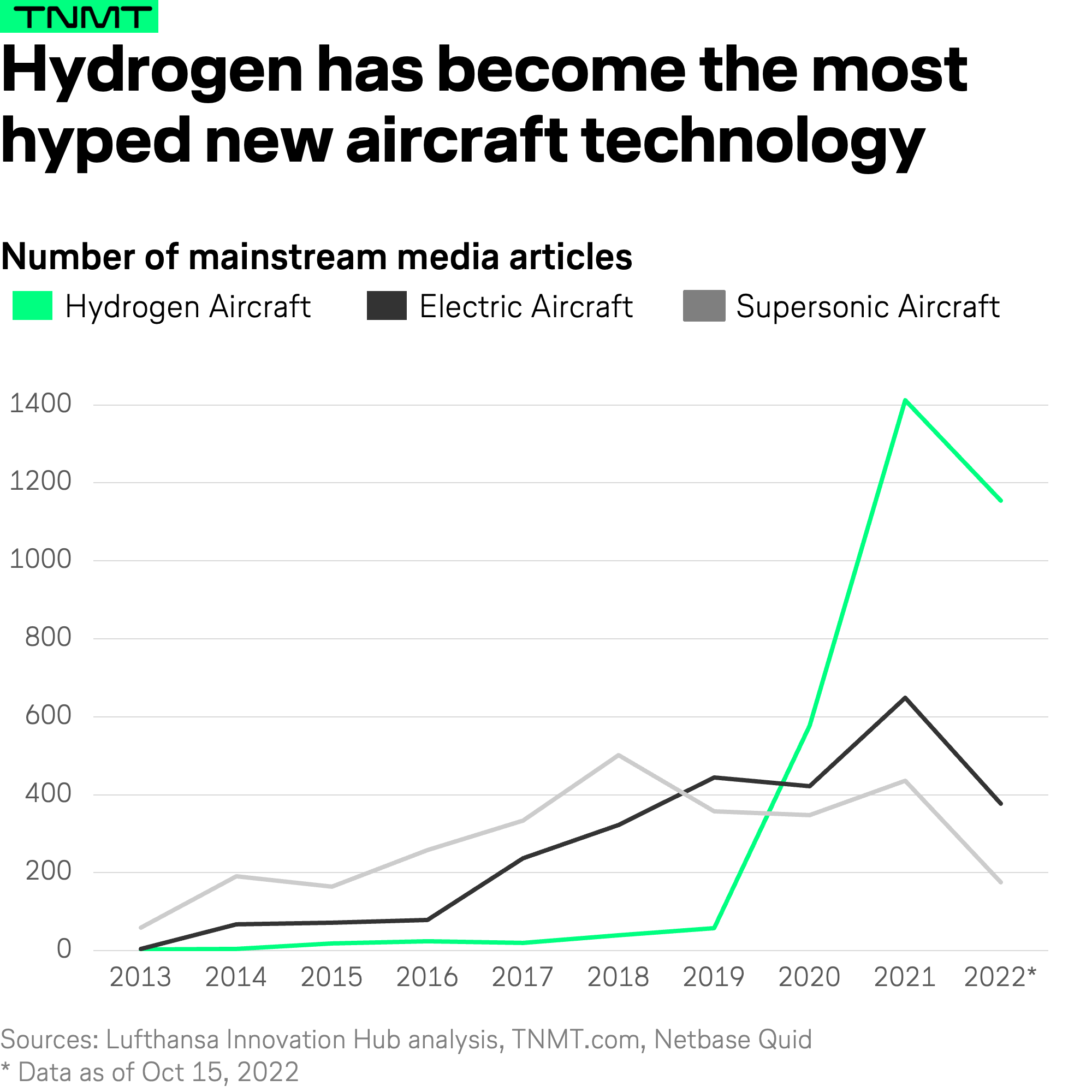

The one-sided media narrative

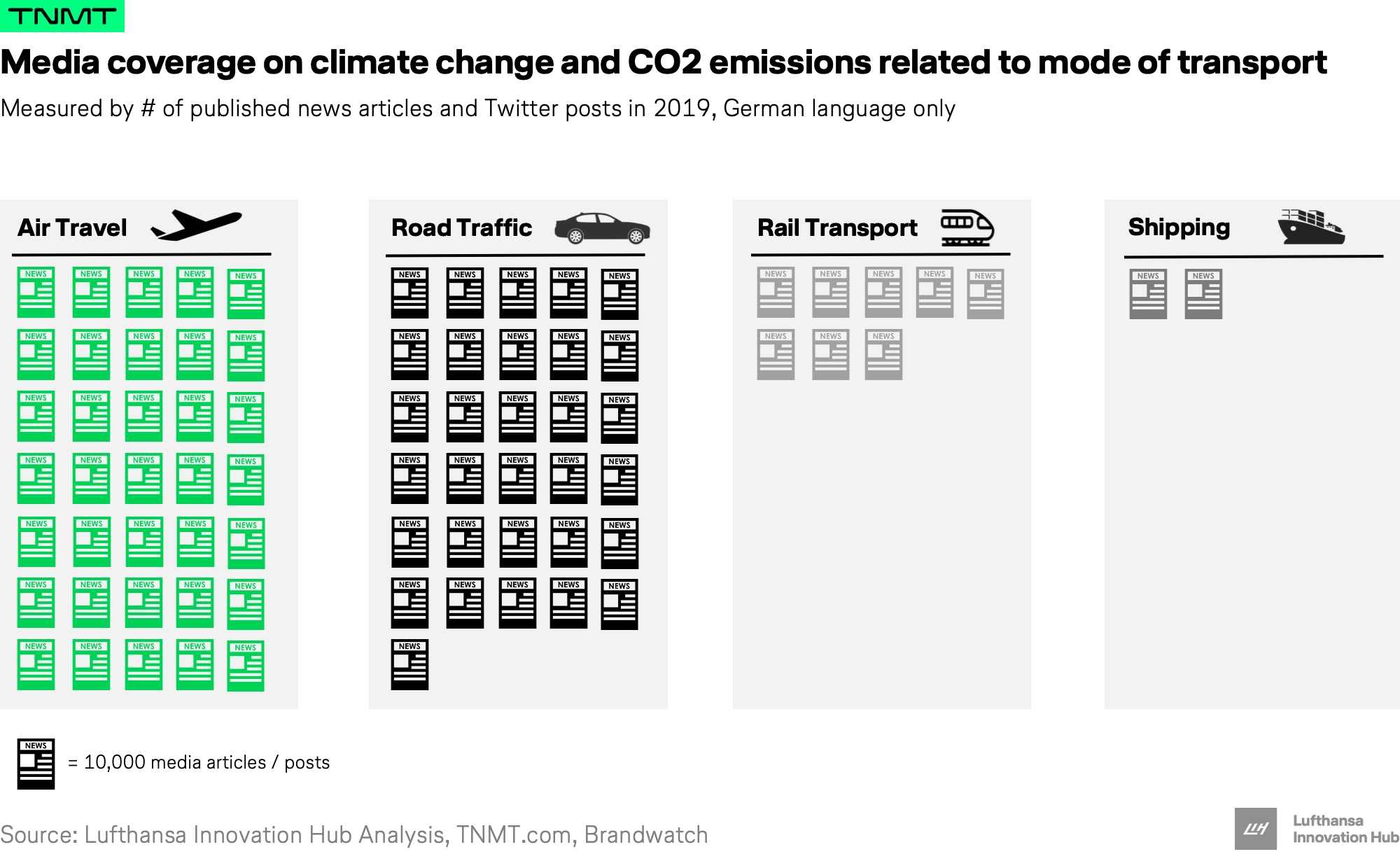

Interestingly, despite road traffic generating the vast majority of GHG, the public narrative seems to focus a lot more on domestic air travel than it should. Let’s look at the data.

We analyzed overall media coverage (incl. social media) by counting the # of articles and tweets related to each transport mode and the term “Emission* and Climate*” in 2019 to identify which segment was discussed most frequently in the media.

It turns out that media coverage related to climate change has disproportionately been associated with air travel (47%).

By contrast, road traffic was discussed 40,000 times less than air travel, despite its huge impact on GHG emissions within Germany, as we saw above. Rail transport and, particularly, inland shipping are almost fully neglected due to the bare minimum of articles and tweets.

The more nuanced view

Conscious decisions on when to take the plane for a domestic trip around the country are critical. But the same standard must be applied when taking the car for everyday errands and activities, like driving to work or visiting friends. It’s all too easy to scapegoat domestic flying as the source of all climate evil.

This one-sided debate is both dishonest and highly dangerous (also for the climate). For instance, consider that out of all the 124 million passengers who boarded an airplane in Germany in 2019, only 20% embarked on a domestic journey and many of these flights were feeder flights used by people to continue their journey to an international destination.

So, only the minority of flights taking off in Germany could really be substituted with alternative modes of transport like the train. And if feeder flights were prohibited, this wouldn’t necessarily mean that passengers would switch to the train – they may just fly directly to an airport hub in a nearby country, or, in many cases, use the car.

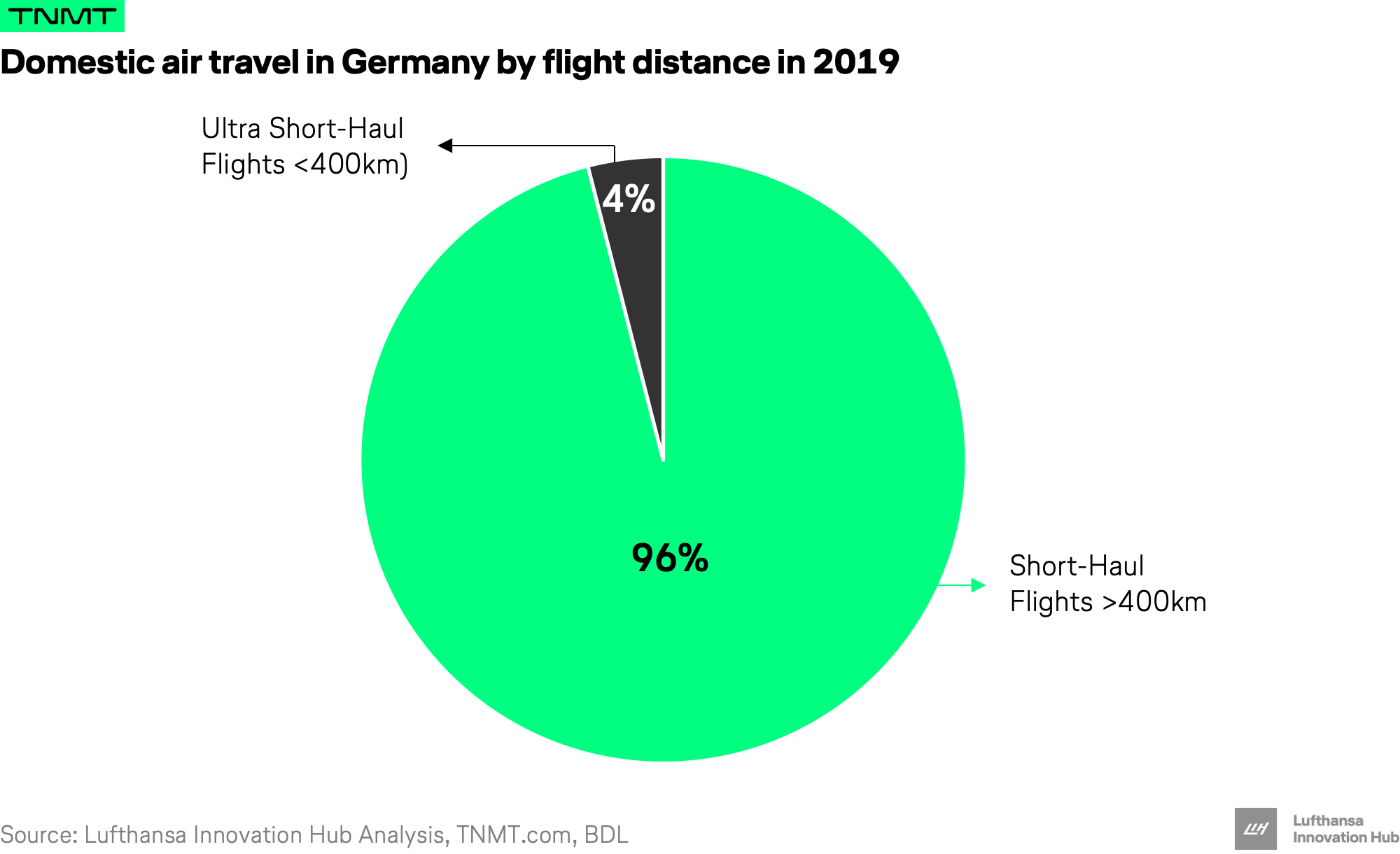

Furthermore, just 4% of the 23 million purely domestic air travelers chose a so-called ultra-short route with a distance of less than 400 km. The remaining 96% cover a longer distance by air – a distance that cannot be reached by train in a reasonable time. This is especially relevant for business travel where saved time equals money.

In summary, the fact of the matter is that the current debate is centered around a very small group of travelers.