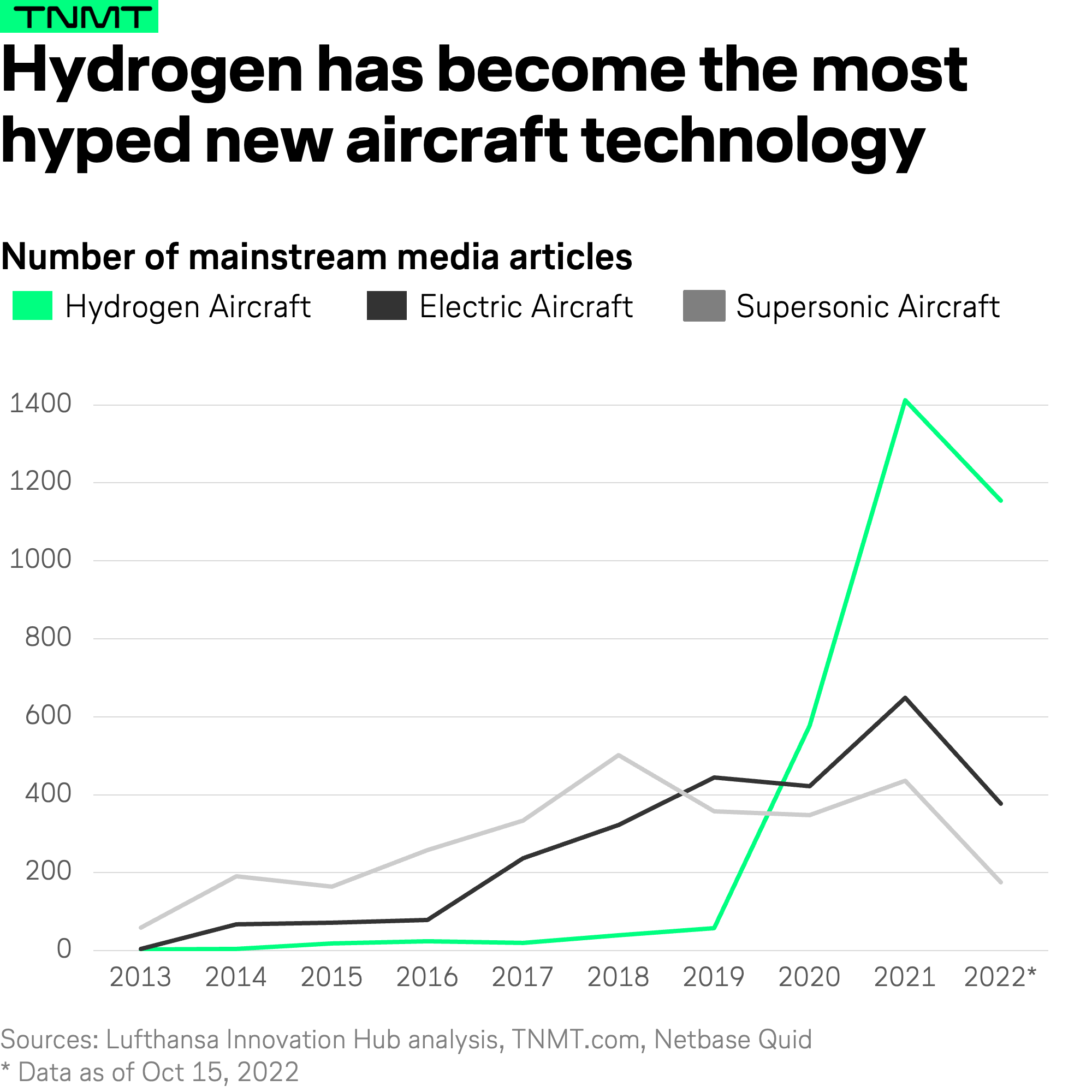

A couple of years ago, when the first reports about the development of electric-powered, driverless multi-copters for passenger transport appeared in the pages of the business and science press, one could have easily dismissed the whole endeavor. After all, at the time it seemed like the slightly crazy idea of some fly-by-night startup founders, who simply wanted to collect money from investors with spectacular promises.

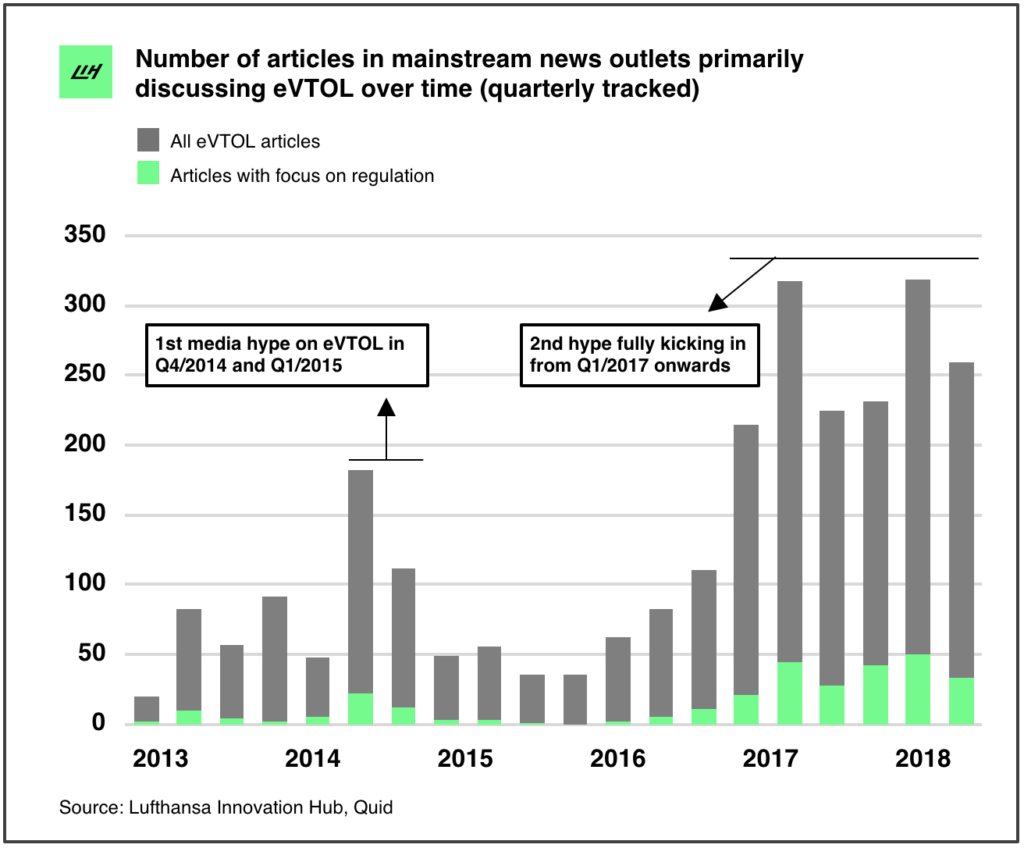

A close look at the most mainstream press landscape shows how the public narrative on “electric vertical takeoff and landing” (eVTOL) greatly intensified in global mainstream news portals in early 2015. But after this turbulent initial euphoria, the interest of the press just as quickly waned. It would take two more years before the hype surrounding air taxis, flying cars, and electric VTOL aircraft would seem to be truly justified.

After countless reports of successful test flights from Kitty Hawk, Airbus’s Vahana, Volocopter, and Lilium, the future of the air taxi now seems closer than ever. Within the next decade, thousands of car-sized drones may be buzzing through the air, bringing business travelers to their appointments while relieving the traffic chaos on the ground.

The hardware development already seems to be largely on track. Lilium recently announced that it will carry out the first manned flights by the early 2020s. However, the regulatory framework, as well as specific plans for the transport infrastructure in the air, are lagging behind. These unresolved issues were barely taken up in the media until the beginning of last year. In light of the aim to make air taxis part of urban reality in the near future, the discussion about airspace regulations and security needs a major boost.

Here are a few ideas to kick things off:

Clear rules for airspace

Before certifications of eVTOL vehicles can begin, solutions for air-traffic management, the airspace structure and, above all, general flight safety must be found. The airspace structure and air-traffic management — i.e. the active management of flight movements by air-traffic control — are not yet designed for the large-scale commercial operation of manned and unmanned aerial vehicles.

For instance, except for take-off and landing, aircraft flying over cities and other densely populated areas may not go below a minimum altitude of approximately 300m (1,100ft) over the highest obstacle. One possible solution could be to define separate flight corridors — analogous to roads on the ground — in which this restriction is lifted. In these corridors, air taxis could either be actively managed by air-traffic control or, alternatively, arrange and coordinate themselves automatically and autonomously.

Obviously, the latter solution would not only be technically challenging, but it would also be necessary to ensure that the air-taxi route does not conflict with the flight paths of other conventional aircraft, most of which fly by sight (e.g. helicopters).

Safety onboard and on the ground

Safety and reliability present another challenge. Solutions here must be found that allow air taxis to be able to make a safe alternative landing at any time — even with the loss of individual systems (e.g. control computers or individual rotors) and without endangering passengers or people on the ground. This is an enormous challenge in urban settings. For this purpose, one could imagine a tight network of suitable emergency landing sites along flight corridors, for example on the roofs of houses and buildings or on suitable open spaces on the ground, which would need to be installed and maintained.

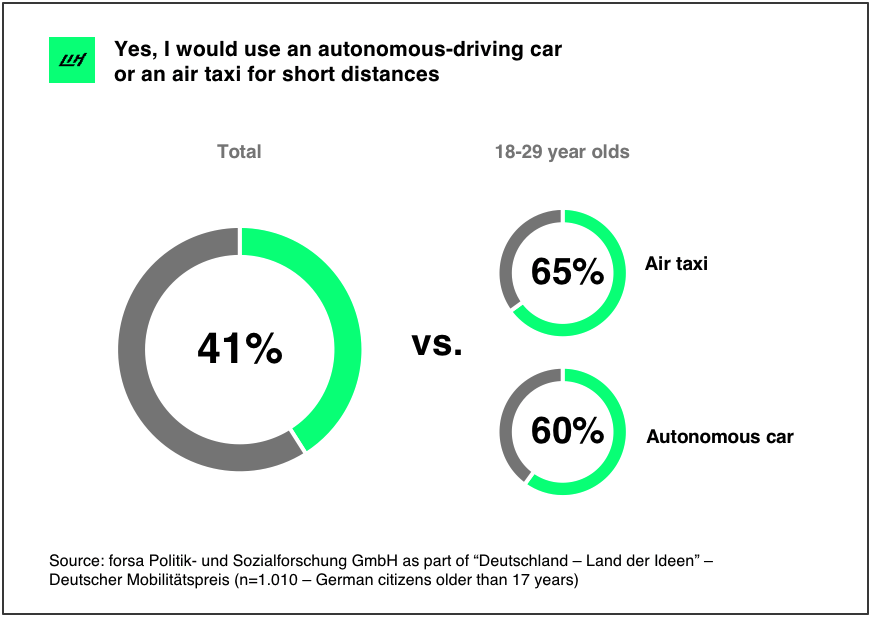

Major security concerns on the user side seem to represent less of a hurdle, even in usually risk-averse Germany. According to a recent Forsa poll, 41 percent of Germans would actually be willing to climb into an air taxi. Younger Germans are particularly open to innovations in mobility. In fact, 65 percent of 18 to 29-year-olds would use air taxis and unmanned drones for short distances. This is even higher than for autonomous cars on the ground (only 60 percent).

To further drive acceptance of the general public, an effective strategy could be to develop strong partnerships between eVTOL manufacturers and trusted brands in the travel and mobility sector. Greater confidence in the product will also result from the presence of a human pilot in the initial introduction phase until about 2035, which we assume will be necessary for safety reasons.

Infrastructure to integrate mobility modes

In terms of infrastructure, the challenge lies in the limited space available for takeoff and landing in metropolitan areas. Moreover, as eVTOL aircraft is supposed to become an integral part of the existing intermodal transport chain, so-called vertiports shall be located at frequently visited inner-city transport hubs in order to connect them efficiently with the various first and last-mile mobility providers (e.g. e-bikes, scooters, public transport). The roof of the new Munich central train station, for instance, will be examined to determine if it can be upgraded for the operation of air taxis

A niche market in the premium segment

No doubt there are existing barriers in commercial implementation that have to be overcome. The market potential will initially be limited compared to existing conventional modes of transportation. According to UBER Elevate, the initial price point for flying taxis will be around $5.73 per passenger mile. This more or less coincides with calculations by a recent study on the future of vertical mobility by Porsche Consulting, which was conducted in cooperation with the German Aerospace Center. The authors of the study assume, for example, that the 30 kilometers between Munich Airport and Munich’s city center could be covered within 10 minutes. The price for the route would range from 100–123 euros.

Unsurprisingly, not everyone will be able to afford these time savings. The new service will initially restrict itself in the urban mobility mix to a premium segment and cover central feeder routes between, for example, city centers and airports or airports and exhibition centers.

First commercial routes to focus on overcrowded cities

In addition, the significantly higher price compared to other means of transport will be especially worthwhile in cities where the transport infrastructure is reaching its limits and the use of longer-distance air taxis will save a considerable amount of time. As a result, vertical takeoff and landing air taxis will most likely first be seen in cities like Mexico City or Chinese megacities.

Currently pointing in this direction is the cooperation between the ride-hailing provider Cabify and Voom, an on-demand booking platform for inner-city helicopter flights, in Mexico City. Users of the Cabify app can simply choose the “Cabify Air” option. Longer distances can then be covered by a combination of a taxi ride and helicopter flight between four centrally located helicopter landing pads in the city.

In such scenarios, eVTOLs are the quieter, less expensive, and technologically superior alternative and will gradually become part of the urban mobility landscape in the 2020s.