Last year, a Paralympic medallist climbed on top of a British Airways plane as part of the Extinction Rebellion, an organization taking action against climate change. And when Greta Thunberg sailed a zero-emissions boat to attend the UN Climate Summit in New York, it was the ultimate public demonstration of the recent movement against air transportation, also known as flight shaming.

As warnings from scientists about the state of human-caused climate change grow more and more drastic with each new report, so does consumer pressure on the aviation industry. Reducing carbon emissions when traveling by plane has now become a major concern for travelers, as evidenced by a surge in Google searches for sustainability-related terms such as “CO2 compensations” and “Atmosfair” or “MyClimate” – two of the leading companies offering travelers carbon-emission offsetting.

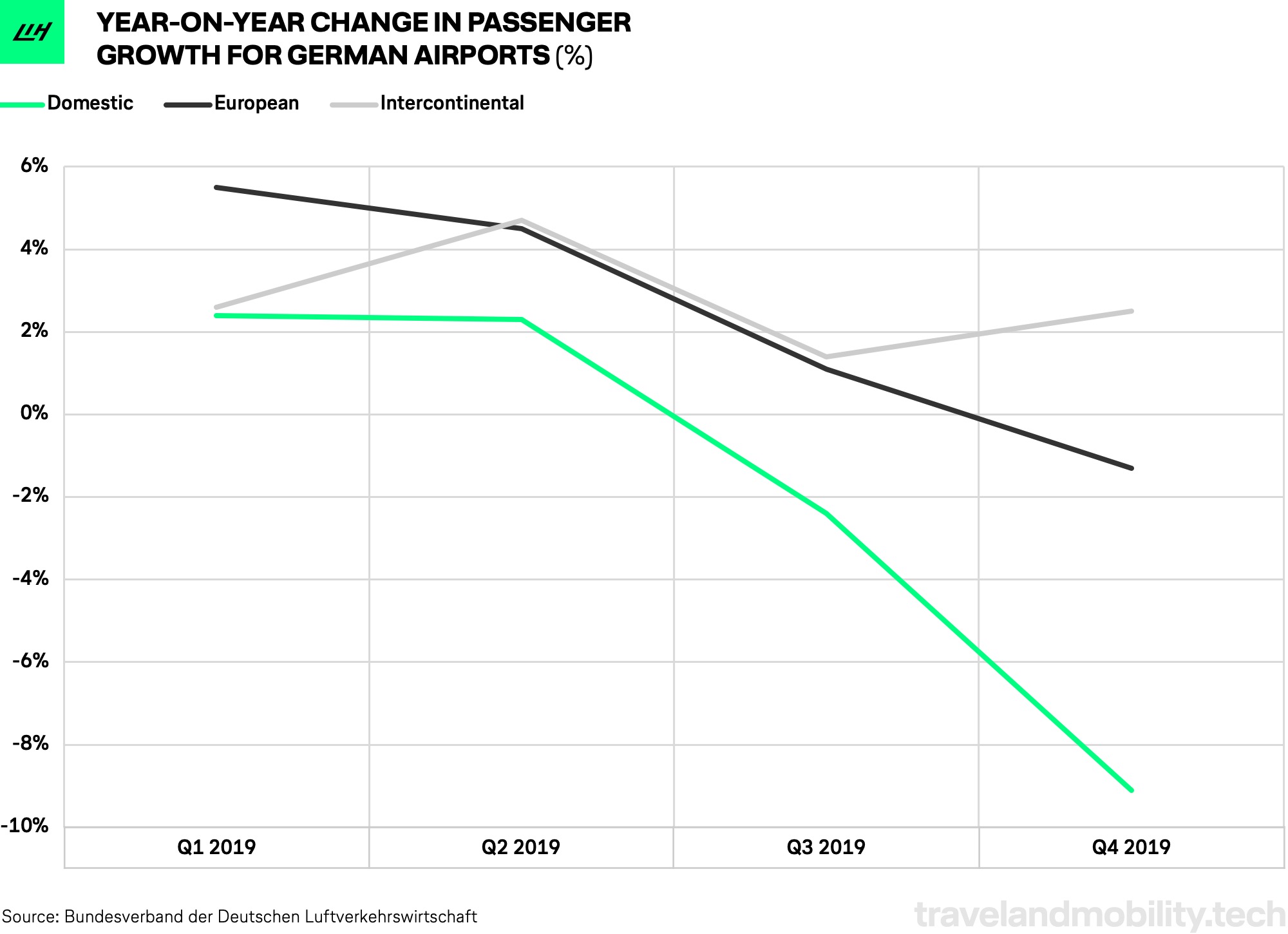

This movement might now even be felt in Germany, where data from the BDL suggests, that demand for domestic flights fell notably in the second half of 2019.

However, this is most likely driven by a slowing German economy and a reduction of overcapacity by airlines. The data for 2020 will first reveal whether demand will truly be affected due to people flying less for environmental reasons.

Travel companies are responding

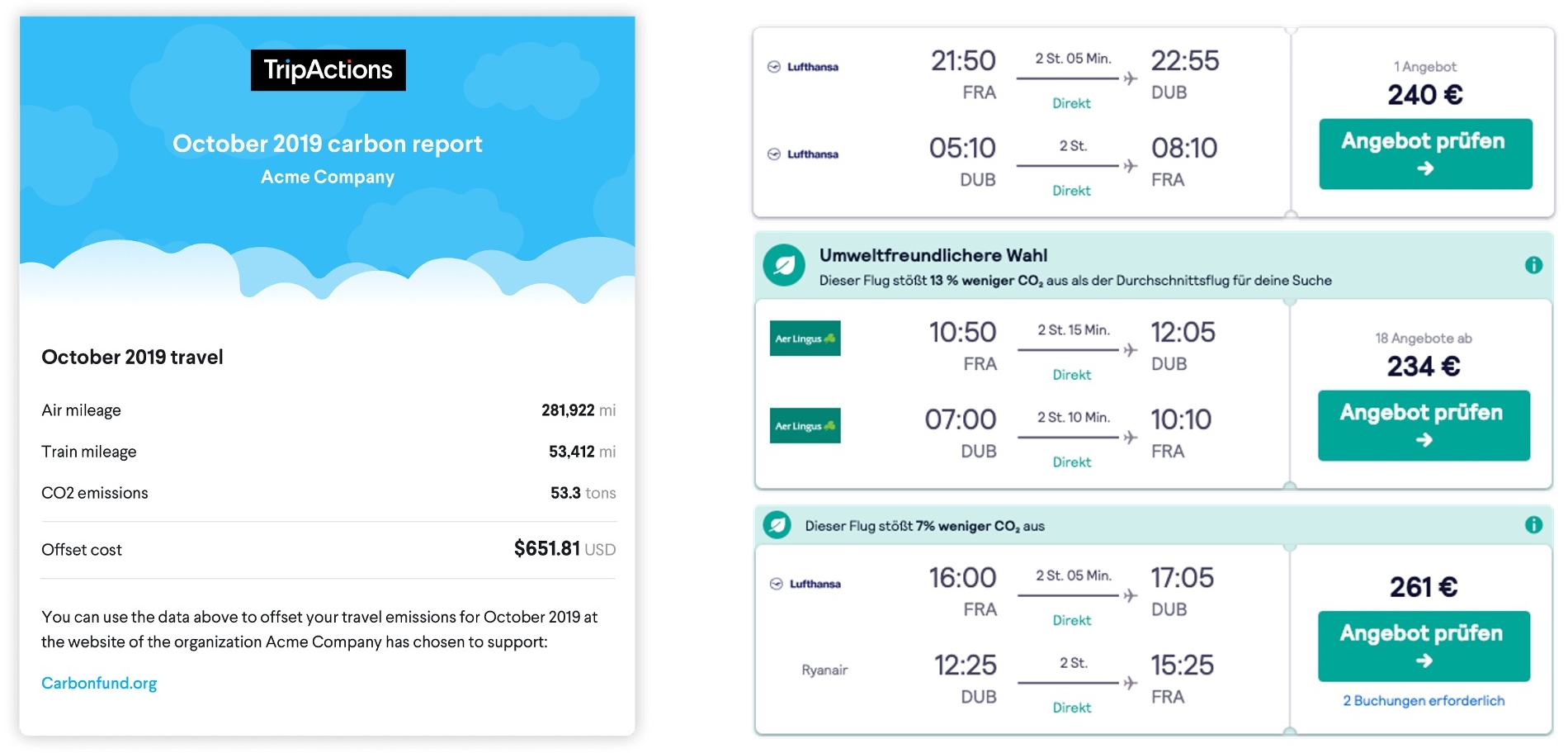

A few travel companies are ahead of the curve in their response to this trend. TripActions, a business travel management startup and one of Travel and Mobility Tech’s unicorns, is one of them. In 2019, they launched a carbon-impact data tool that visualizes the environmental impact of a company’s business travel and suggests options to reduce this impact – for instance, by offsetting emissions. According to their CEO, Ariel Cohen, providing transparency on a company’s environmental impact is the crucial first step in incentivizing a change in behavior.

Similarly, the well-known meta-searching site Skyscanner now offers users a glimpse of their own carbon emissions by showing “green tags” in their search results. These tags highlight more sustainable routes for passengers who are interested in eco-conscious travel.

Right: Skyscanner showing green tags in their search results

Also airlines are making efforts

Mainstream aviation companies are also attempting to make strides in reducing their carbon footprint. Our parent company, the Lufthansa Group, has long been offsetting all duty travel flights of its employees. Furthermore, all corporate customers will fly CO2 neutral from 2020 on.

In November 2019, easyJet made headlines when they announced their plan to offset all their flights going forward, becoming the first airline to fly carbon neutral. While the effort seemed radical, the move was met with criticism that it was a greenwashing stunt rather than any meaningful change in the airline’s own carbon emissions – similar to Ryanair’s most recent environmental campaign that was banned by the UK Advertising Standard Agency for misleading consumers as the airline had failed to substantiate its environmental claims.

Still, the above trends and actions suggest that travel industry players are rushing to take multiple actions to mitigate their environmental impact. Clearly, sustainable travel with fewer carbon emissions is the path forward for the aviation industry.

Current research studies miss an important area

Every day, we’re seeing more studies and in-depth press articles covering the topic of sustainability, especially in the travel context.

However, most of these articles tend to predominantly look into a single topic of study: the growing awareness in people’s minds surrounding “greener” travel. While many of these studies found out that people say they want to travel more sustainably (e.g. here or here), they don’t offer concrete numbers on how travelers’ words translate into action.

We believe this is an important area to look into because there usually is a major difference between reported behavior (what people say they do) and actual behavior (what people truly do) – a common phenomenon that is backed by decades of research.

Our approach sheds light on what travelers say vs. what they do

Based on this glaring gap in today’s research, we wanted to draw a data-based, holistic picture of the likelihood of travelers paying for sustainable travel, specifically comparing their intentions versus actions. We wanted to find out whether plans for sustainable travel are actually realized, whether people end up putting their money where their mouth is, and to what extent, if any.

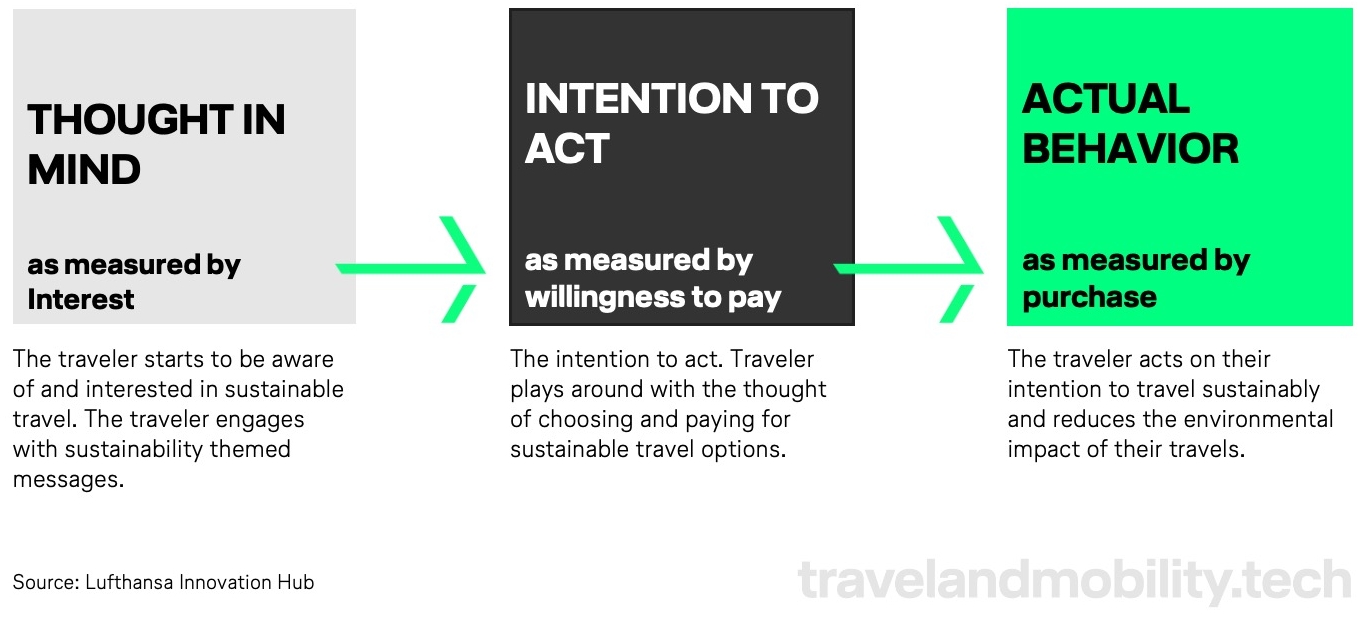

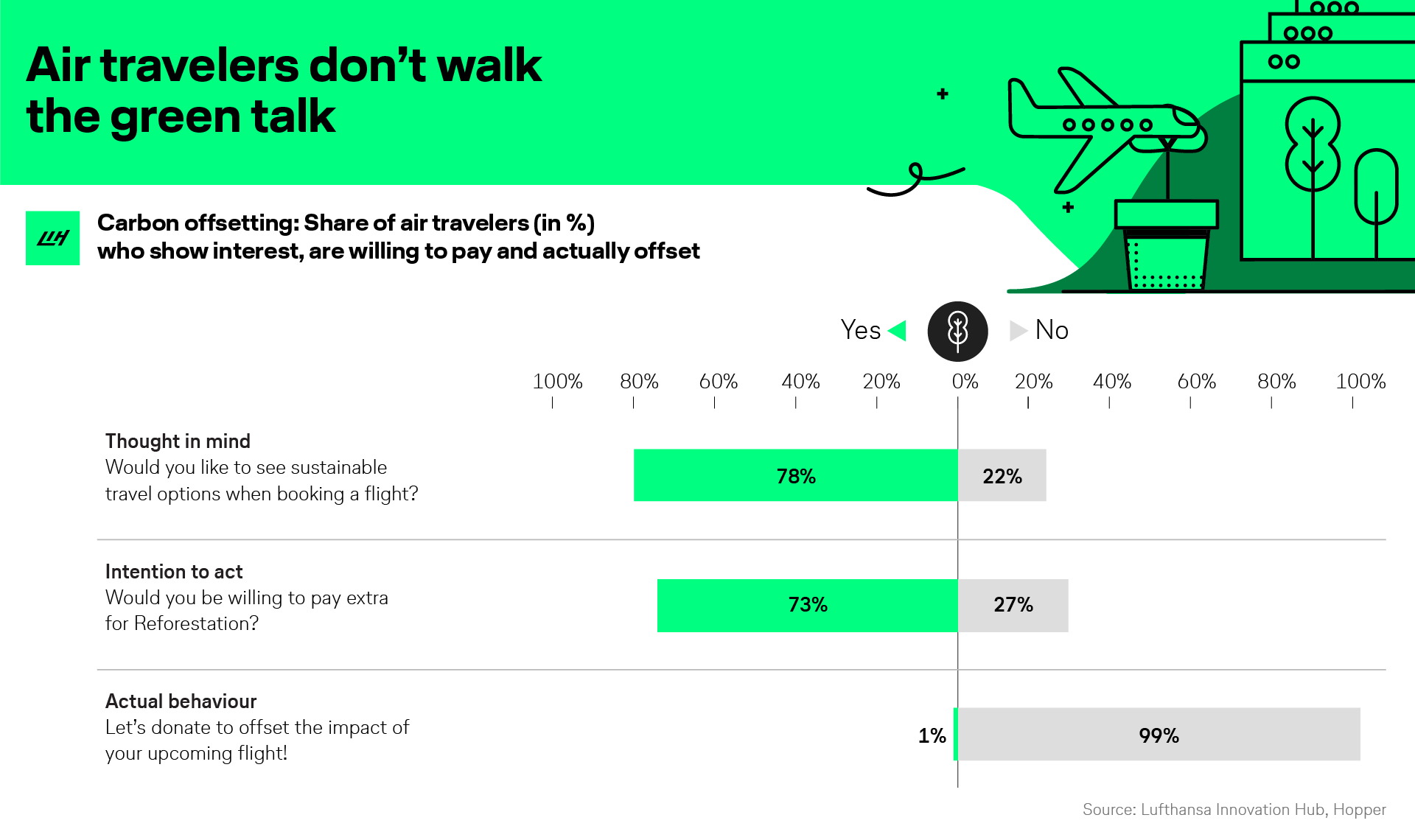

In order to do this effectively, we developed a framework to address the entire mental process for travelers, breaking it down to three distinct steps:

- Thought in mind: Starting with awareness of and interest in sustainable travel

- Intention to act: The willingness to choose and pay for greener travel options

- Actual behavior: Booking and paying for sustainable travel

Clearly defining these three steps helped us differentiate between the different thought processes a person goes through before they pay for something. The framework also made it easier to measure the effects. We conducted an experiment for each of these three “mental steps” (see above) and compared them to one another, measuring conversion rates and potentially discovering where we lose most people.

Methodology and scope

We put our heads together with the Data Science team of airfare specialist Hopper. To date, the Hopper mobile travel app has been downloaded more than 45 million times with 150,000 new trips being planned in the app each day. Hopper’s user base enabled us to leverage a large pool of real-world travelers to test our experiments and validate them.

We believe that our sample audience is representative of the online travel-booking market. With nearly five million active users per month (according to App Annie in 2020), the Hopper user base is diverse in terms of age, geography, distance flown, etc. Thanks to Hopper’s numerous filters such as quickest or cheapest flights as well as add-on services that you can buy on top of your travel bookings, we were able to encompass variables such as preferences for a flight and differentiate between users that are time-, price-, sustainability-, or comfort-oriented. As such, we believe our findings are relevant for all airlines and travel providers from various locations, including both premium and low-cost carriers.

We conducted a total of three experiments, one for each stage of the framework described above. Across all three experiments, we were able to reach about ten thousand users. The experiments were conducted by sending lock-screen push notifications to existing Hopper app users. Here’s an example:

If yes: The user is led to a survey (e.g. “Would you like to see more sustainable travel options when you book?“), or nudges that call for action (e.g. “Hey there! Travel is great, but airplane emissions not so. Help offsetting the environmental impact with a tree-planting initiative!”).

We also ran the experiments during different points of the travel-planning journey: pre-booking and post-booking. Additionally, we separated results based on location – more precisely, between US and EU-based travelers.

Now with our methodology explained, here are the experiments and the respective results.

Experiment 1: Sustainable travel as a thought in mind

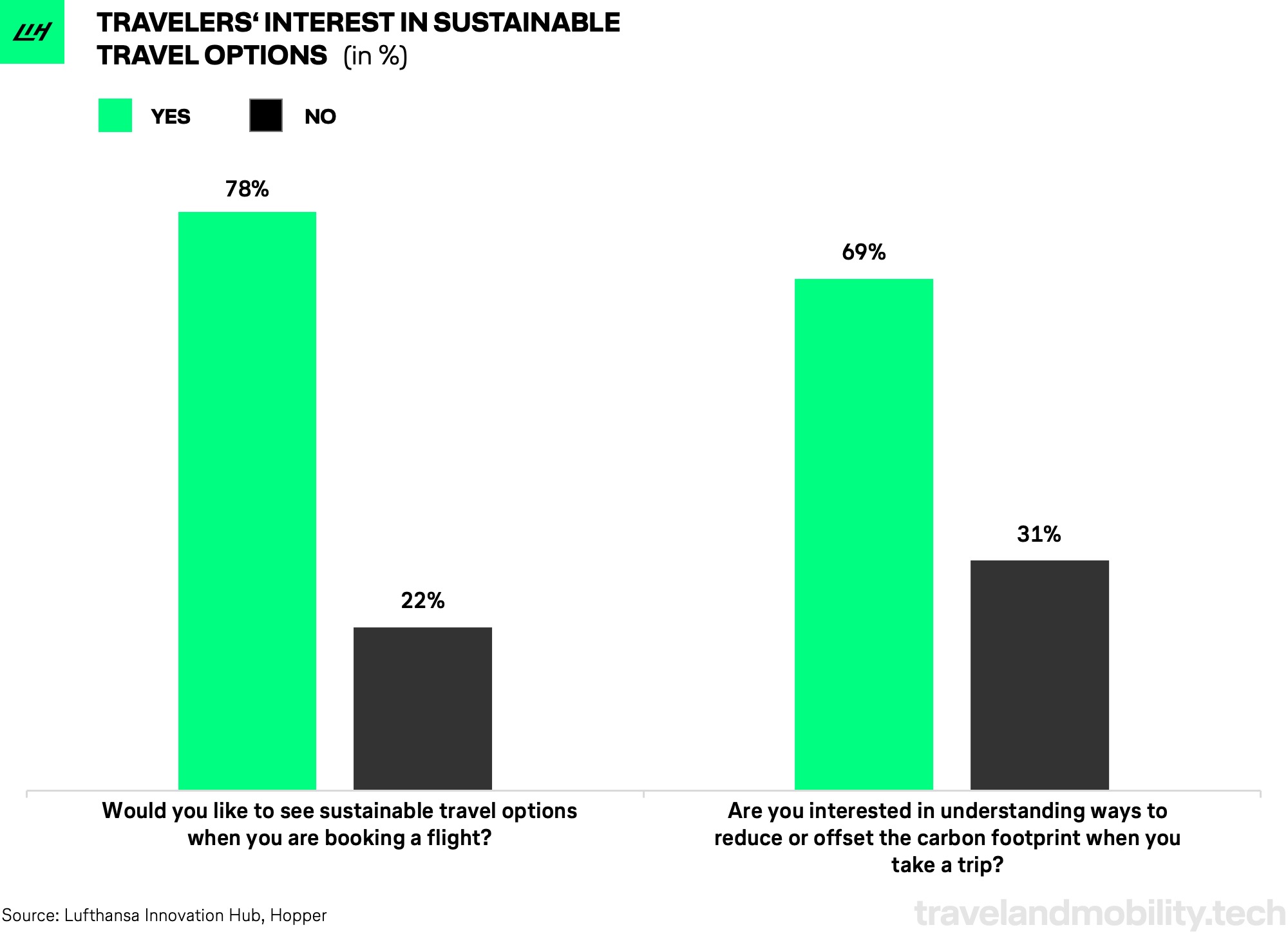

This initial experiment stemmed from the first block in our framework – thought in mind. At this step, we wanted to understand air travelers’ general awareness of and interest in sustainable travel and thereby quantify the potential demand. Demand was measured with these two variables:

- Interest in seeing sustainable travel options when booking a flight, and

- Interest in learning more about these solutions.

Methodology: For this experiment, we asked two questions (based on the variables mentioned above):

- Would you like to see sustainable travel options when you are booking a flight?

- Are you interested in understanding ways to reduce or offset the carbon footprint when you take a trip?

Each question was sent to a different sample group using the concept of random sampling, where each user had an equal chance of being selected for the sample group. Here are the results:

It turns out: 78% and 69% answered yes. We can confidently conclude that there is sufficient demand with about ¾ of users seeking sustainable travel options.

Disclaimer: There could be bias in the data since people might feel unconsciously pressured to respond more positively to care about sustainability (see so-called social desirability bias). Yet the percentages are high enough to perceive it as a preference, thus creating a legitimate demand for booking or purchasing more sustainable air-travel tickets.

Experiment 2: Intention to act towards sustainable travel

Since interest is merely the first step on the way to action, we then tested a user’s intent to pay for sustainable travel alternatives. This is distinct from pure interest, as it requires a certain level of engagement, e.g. clicking a notification to find out more about how to travel greener.

To make this more tangible, we asked travelers about two concrete solutions to more sustainable air travel that currently exist:

- Fuel-efficient aircraft (FEA)

- Planting trees (reforestation)

The former solution offers flying with a more modern airplane model that has a lower emission release because it burns fuel more efficiently. The latter solution gave users the option to plant trees to make up for their emissions.

Methodology: As in the first experiment, the audience was randomly selected for each travel alternative (FEA or reforestation). We chose these two alternatives because they are some of the most commonly implemented industry solutions today.

To combat the potential effect of prices affecting users’ answers, we offered price amounts ranging from as little as 5 to 150+ (in local currency) and let the participants set the price themselves. This allowed us to isolate and measure “intent” in its purest form.

The questions we asked were as follows:

- Would you be willing to pay extra for <green travel alternative>?

- If yes, how much?

Option I: Picking flights in a more fuel-efficient aircraft

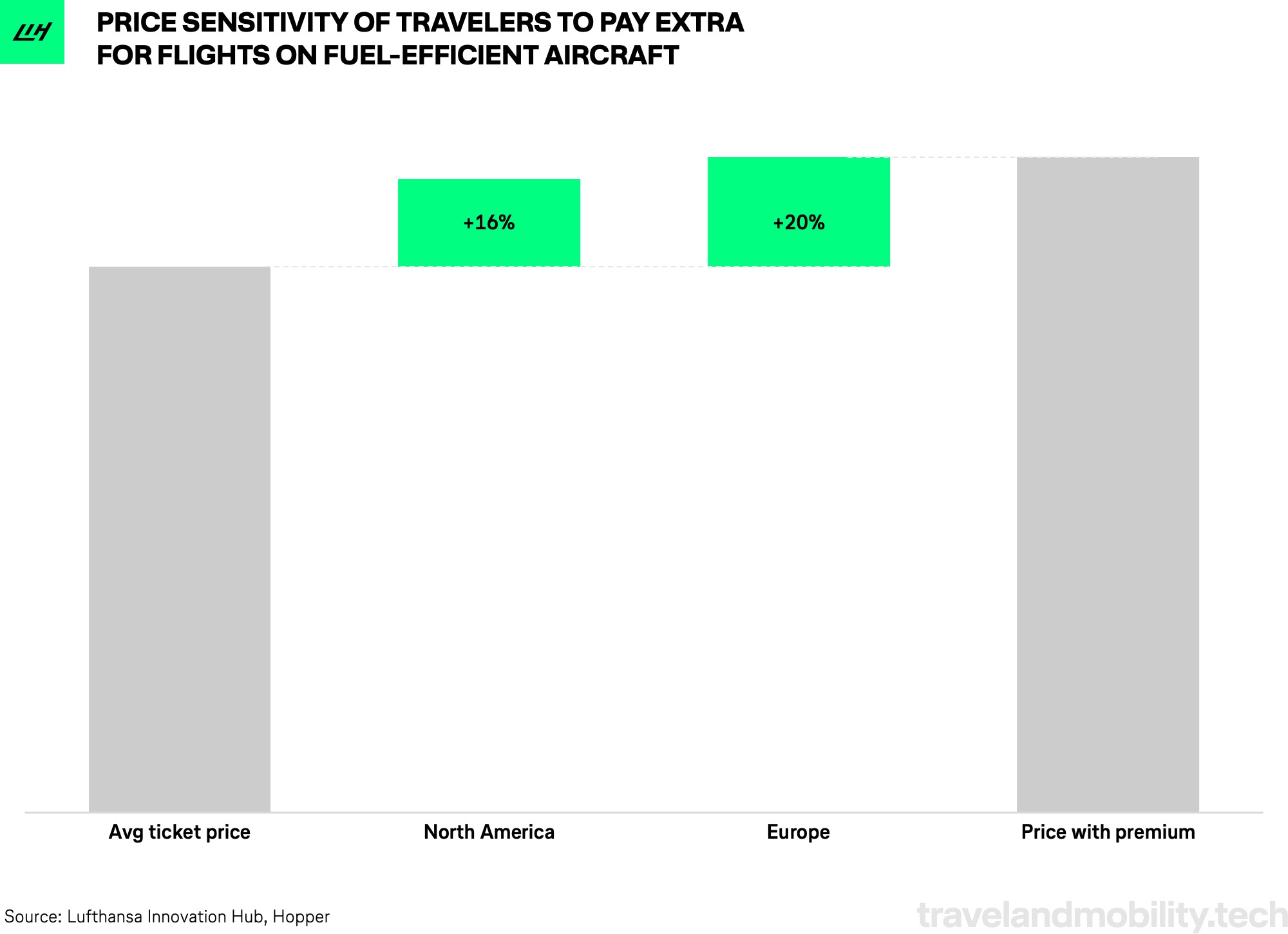

Our main objective for this experiment was to find out whether people would intentionally choose a flight because it was operated on a more fuel-efficient aircraft.

Within these parameters, the results were:

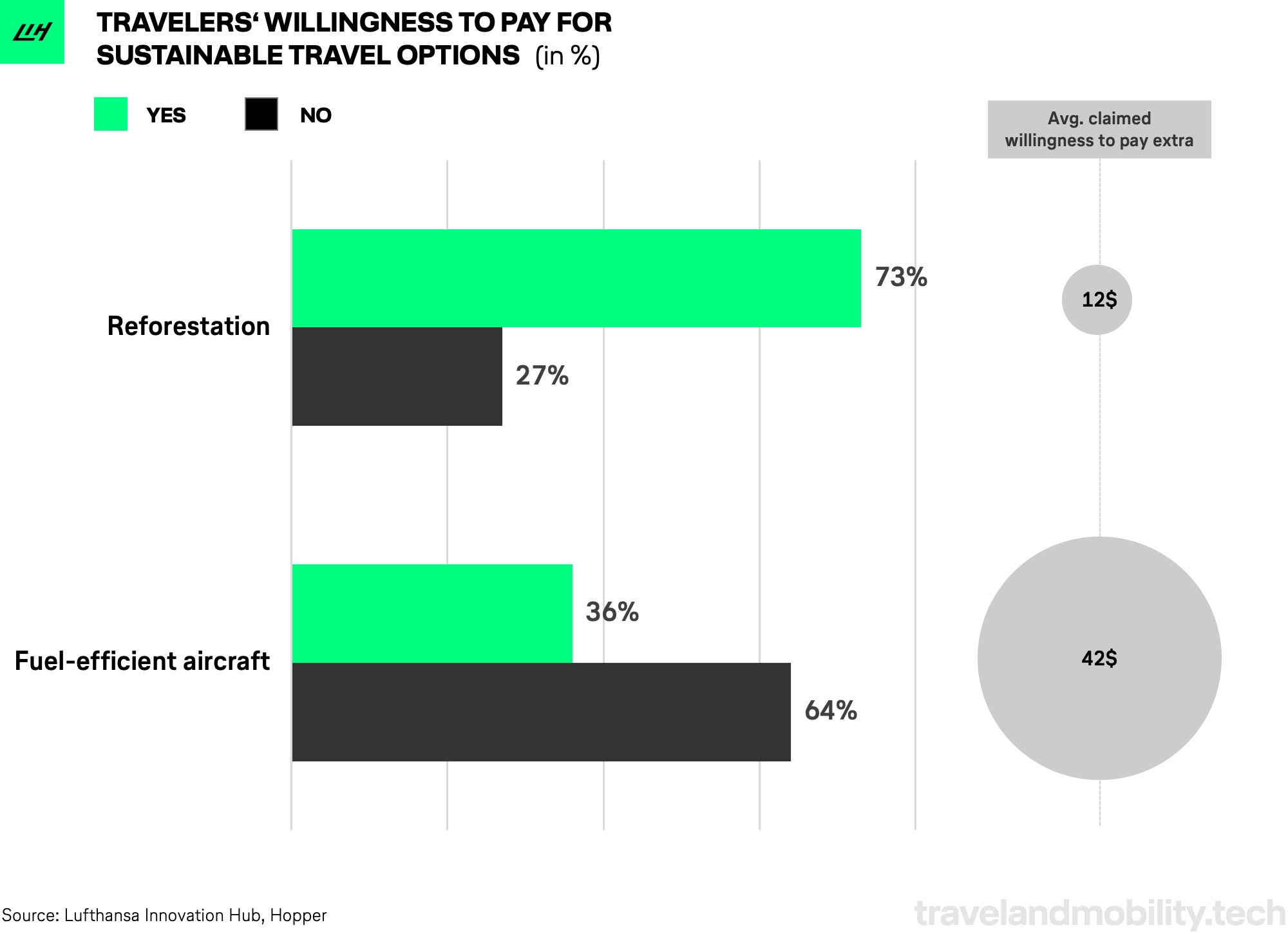

- 36% of users said they would be generally willing to pay for flying in a fuel-efficient aircraft.

- On average, users would pay an extra $42 on top of an average ticket price.

Our first notable finding is that there seems to be a significant difference between the users’ willingness to pay (intention to act) vs. interest in sustainable travel options (thought in mind). While a vast majority – about two-thirds – of surveyed users indicated an interest in seeing the options, only about one third say they’d be willing to pay more for fuel-efficient alternatives.

However, we need to take into account that a fuel-efficient aircraft is not a familiar concept for many people because it is a very industry-specific development. Most users would not necessarily know how FEA works or what it might look like for passengers. Therefore, despite the significant drop in interest, it is still good news that people are actually willing to pay extra for a rather ambiguous yet sustainable solution.

Furthermore, the $42 amount translates to about a 16-20% premium on the average plane ticket purchased by surveyed users, which is quite a high percentage and also a good margin for airlines to work with. Overall, we consider this to be a positive outlook.

Option II: Offsetting emissions via reforestation

For the second sustainable travel alternative, reforestation, we asked the same questions and got these results:

- 73% of users claimed they would be willing to pay extra to offset the impact of their travel through tree planting.

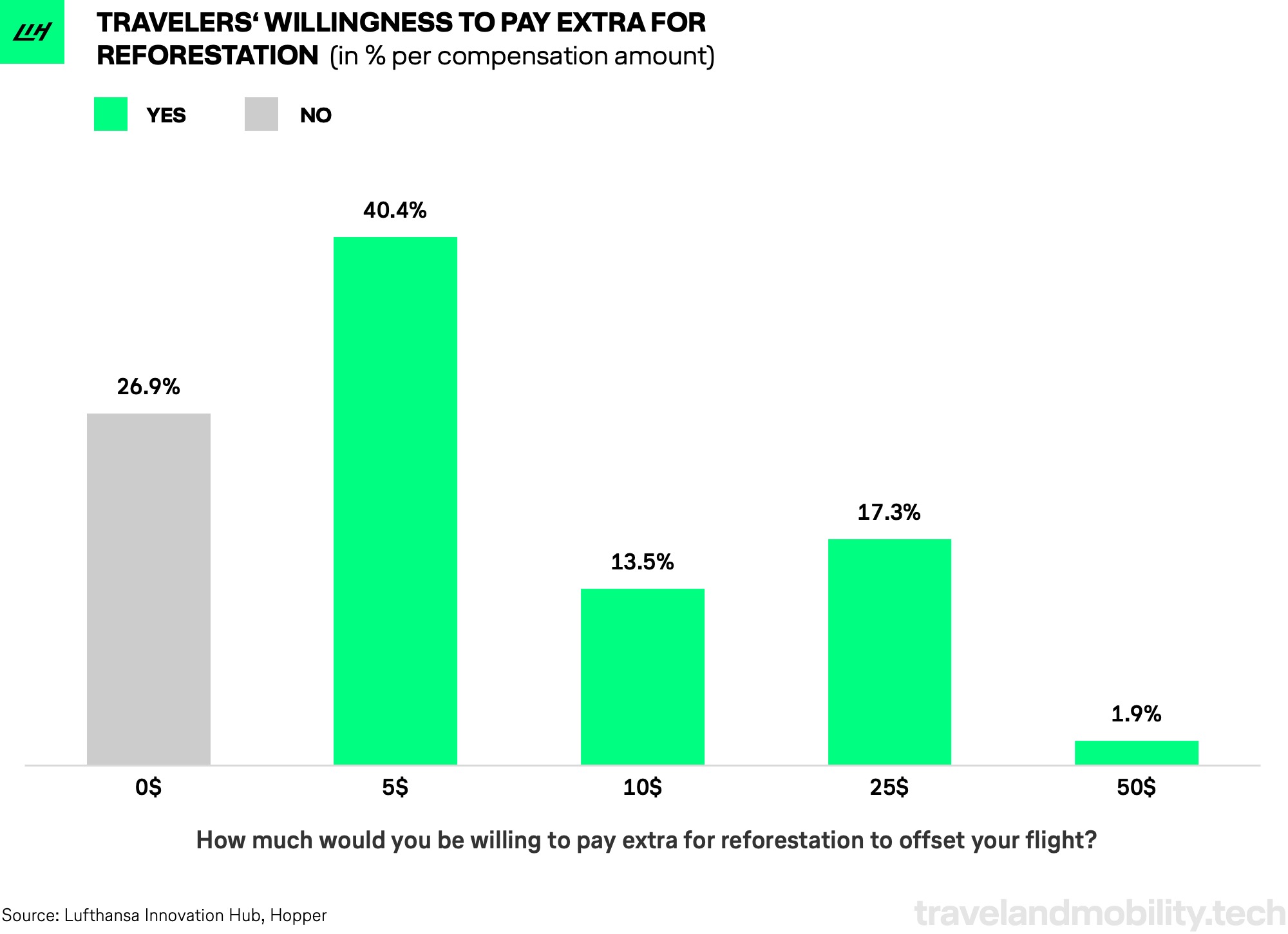

- But the vast majority would pay only $5 extra for reforestation.

These results illustrate that the willingness-to-pay factor (intention to act) is nearly double for reforestation as it was for FEA, which we assume is because tree planting is a more tangible concept to travelers than fuel-efficient aircraft. There’s less need to explain what tree planting is or how it would benefit the environment while it’s probably a lot harder for travelers to put a price tag on a less-known concept such as FEA.

But while there is a high interest in paying more for reforestation, the extra amount people say they are willing to pay is a lot lower in comparison to the premium for FEA. Out of the 73% that claimed to be willing to pay extra, most said they would be willing to pay only $5 (40%), followed by $25 (17%), and $10 (14%). Thus, the average premium is 12$ for reforestation as compared to 42$ premium for FEA.

In summary, here are the results for both FEA and reforestation at a glance:

We conclude: the overall outlook is quite positive in both cases. We assume there is a significant audience and demand for sustainable travel choices. We also expect this number to increase with more media coverage, political action, and initiatives from travel companies themselves.

Experiment 3: From willingness to action

For the last step in the buyer journey, we wanted to know whether users would actually act on their words (actual behavior). This is the most crucial step. To find out, we simply asked air travelers to pay. For this experiment, we only tested conversion to payment for reforestation because at this point we are unable to let travelers choose what aircraft they can fly on, e.g. fuel-efficient aircraft.

Methodology: We sent notifications to users who had booked a flight with Hopper within the previous 24 hours. The notification prompted users to compensate for their flight emissions by planting trees.

Again, we gave them the freedom to choose how much they’d want to contribute since we wanted to test the conversion from ‘willingness to pay’ to ‘action’ and did not want the price to affect this potential conversion. To make the compensation amount more tangible, we also added the number of trees they could plant with their respective contribution. Here’s the notification text we used:

Hey there!

Travel is a great way to see the world, but emissions from airplanes can have a negative impact on the environment. A simple way to help offset the environmental impact of flying is to contribute to a tree-planting initiative!

Would you like to donate to offset the impact of your upcoming flight to <destination>?

- Yes! $5 (1 Tree)

- Yes! $10 (2 Trees)

- Yes! $25 (6 Trees)

- Yes! $50 (12 Trees)

- Yes! $75 (18 Trees)

- Yes! $100 (24 Trees)

- No, I’m not interested in donating today.

Until this point, our experiments all showed positive outcomes. But now it came down to whether travelers would actually put their money where their mouths are. And the results are surprising, if not shocking: out of all the users to whom we sent the notification, only 1% of travelers actually engaged and ended up donating.

To put the results of our three experiments into one overview, here the direct comparison:

Relating back to our framework introduced at the beginning, the results clearly outline that air travelers don’t act on their intentions and words since only 1% of them actually ended up offsetting their carbon emissions.

Conversion rates in other experiments are equally low

To benchmark our findings, we analyzed the compensation data points from two major international carriers (also based on offsetting via reforestation). The conversion rate from engagement to successful compensation was equally low, ranging from 0.29% to 1.10% max. From this, we conclude that our 1% conversion rate seems to be typical for air travelers these days.

We also benchmarked our findings to a study on sustainable travel by the German Federal Ministry for the Environment. Their findings were slightly more positive: They found CO2 compensation rates for 2019 to be 6% and 2% for short-haul and long-haul flights respectively. However, these data points, sourced from MyClimate and Atmosfair, also surveyed travelers who get their flights compensated by their employers. In our experiments, users had to pay out of their own pockets. So we can assume the higher conversion rates are due to the German Ministry including business-compensated travel. With that in mind, we’ll assume that the current industry average for emission compensations is around 1%.

Real talk: Travelers don’t put their money where their mouth is

Compensation rates of 1% really surprised us because there are many survey findings of how people eagerly want to travel more sustainably. According to a Booking.com study, three quarters (72%) of their participants think we need to act now (in 2019) to save the planet for future generations, 50-60% of the German population would like to plan their holidays more sustainably, and Microsoft Advertising reported that 20% more Brits want to book more sustainable holidays in 2020 because they are environmentally conscious.

With factors like flight shaming, growing public outrage, and the increase in media coverage, we expected a higher conversion rate from intention to action. However, that wasn’t the case. This can be due to a number of factors, such as not being offered enough convincing alternatives. Yet with regards to flying, the results are clear – interest in sustainable travel doesn’t convert to behavior in spending habits (yet).

What to do about it? Travel providers and airlines can trigger travelers to act on their words

Even though the mismatch between stated intentions and purchase behavior by travelers is massive, they are not to blame for everything. Our experiments and market observations make us believe that certain tactics by travel providers are urgently needed to convince more travelers to act and pay a premium for greener travel. Let’s go through all four of them in detail:

1. Convenience and context matter

In an earlier experiment with Hopper, we tested whether travelers would be willing to switch from non-direct to direct flights since non-stop flights emit less CO2 emissions. We achieved an impressive conversion rate of 21%, which is significantly higher than the 1%-conversion rate mentioned above. The major difference with this experiment was convenience. Picking a direct flight over a stopover flight always results in time savings. It’s not far-fetched to assume travelers were willing to pay a premium to save time and hassle rather than in order to reduce carbon emissions.

Another important factor to note is that this earlier experiment was conducted on Earth Day, where we used the environmental context to encourage users to reflect on both their expenditure and behavior. People may have felt more conscientious during this time compared to other days.

Our takeaway: airlines and other travel providers should think about how they can leverage side benefits relating to convenience and context in their current offsetting programs to generate higher conversion.

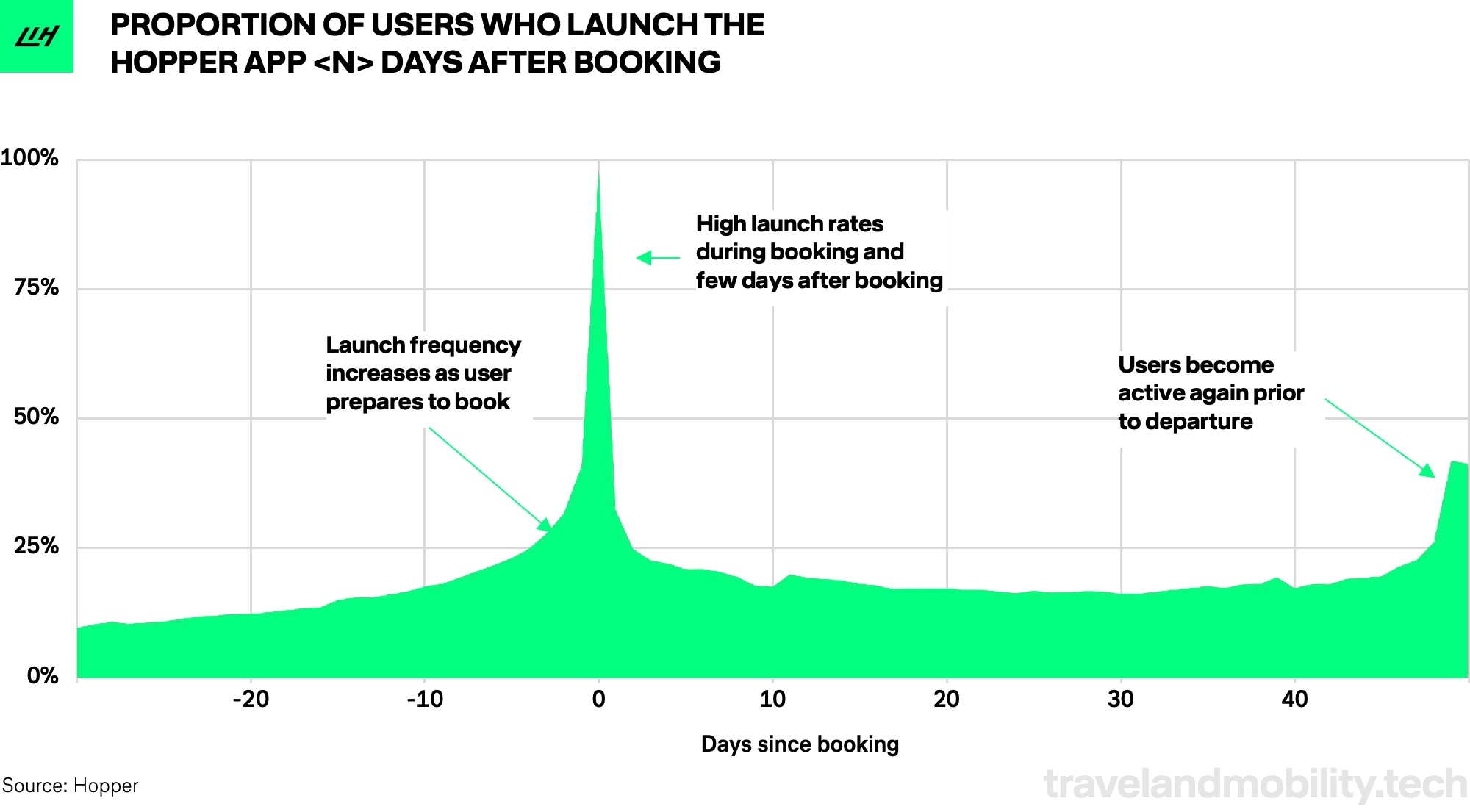

2. It’s all about timing

It turns out that when we engage travelers during their booking journey plays a crucial role in whether they’ll act on their intentions to travel more sustainably or not.

The graph below illustrates that airlines and online booking platforms have two highly important time frames for engaging with users:

- During booking, when their mind is fully focused on the trip.

- Right before departure when travelers come back for information on flight details.

During these steps in the travel journey, most users actively engage with the travel provider and offer travel companies the biggest windows of opportunity to engage and convert customers from intention to purchase to actual behavior.

The booking flow itself offers the best timing in our opinion. We found that if a compensation prompt was sent out after the user had already booked the trip, it had lower engagement rates compared to when the prompt was integrated directly into the booking flow.

3. Urgency and visibility are crucial

Many airlines already offer carbon-offsetting schemes. However, they usually place these offers at the very bottom of the page, or “hide” them somewhere very hard to see. Some airlines even make the user come back after they’ve booked their flight, then take them to a completely different, compensation-dedicated website.

Consequently, we can’t really blame the flyers for low engagement when sustainable travel options are lost in the sea of other offers such as hotels, car rentals, and travel insurance. If users don’t notice the options, they won’t take advantage of them.

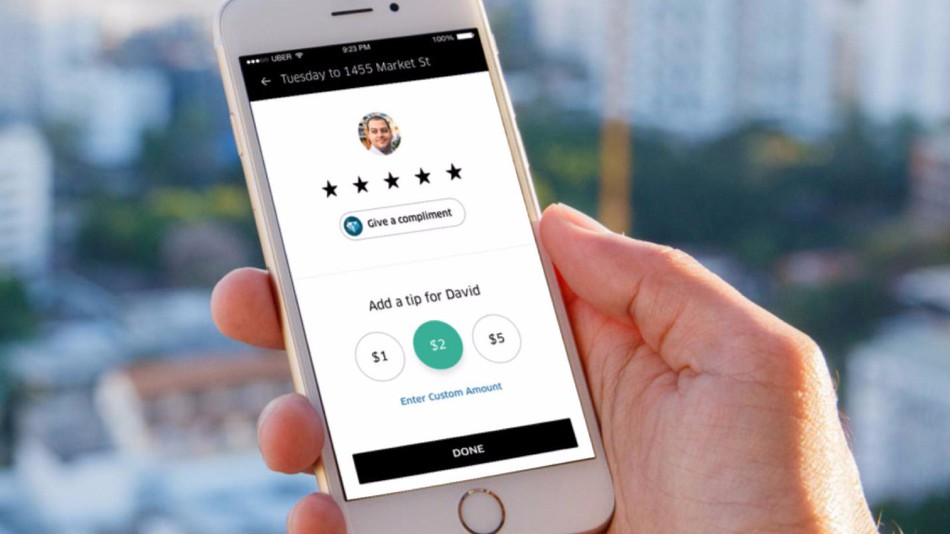

One thing is certain. Companies need to make it less painful for users to find sustainable options. If we create a new way of integrating these offerings, such as placing them on a separate screen with engaging graphics, payments are likely to increase. To illustrate this, we can look at Uber as an example. Their intuitive user interface makes it super easy to tip drivers, which boosts conversation rates for tipping on the platform.

After you finish your ride on Uber, you get to see a screen that asks you to evaluate your ride and tip the driver. While the tip is optional, the platform has embedded the process so seamlessly within the rating flow that users don’t have to go out of their way to think about it anymore. It’s a split-second, yes-or-no decision. The flow also makes tipping feel almost mandatory and uses the positive effect of social pressure. Are you giving the driver five stars? Why not tip them as well?

The history of tipping in the ride-hailing space can serve as a real blueprint for how travel providers can gradually change customer behavior. Uber introduced in-app tipping in 2017. The strategic position and prominent visibility of the tipping screen was such a seamless integration, it started a tipping culture. Only a year after, US drivers earned 600 million USD in tips. This number more than doubled to 1.4 billion USD in 2018. If we pair this number with the increase in the number of Uber trips in the US in 2017 and 2018, this brings the average tip per trip from 0.6 to 1.07 USD respectively in just one year. Uber proves there is a way to use design to encourage specific customer behavior by doubling its tip per ride in one year.

We believe airlines and travel booking sites can draw a lot of learnings from this. Viewing it from the lens of tipping, for instance, it’s not infeasible to tip a travel provider for doing their services well or differently – being greener in this case. If airlines and travel providers want to have a true impact, they should find ways to push more expensive but eco-friendly travel options into people’s faces more aggressively by making things more visible. Ultimately, this is what we believe – companies need to make the process of carbon offsetting more painless for users through seamless integration within the booking flow.

4. Awareness and knowledge of sustainability needs to be raised

In a survey conducted with the online compensation platform Compensaid – launched by our colleagues at the Lufthansa Group – we found that users who were more aware of the benefits and immediate impact of sustainable travel options – in this case, Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF), which is a form of bio kerosine – donated higher amounts on a more frequent basis than users who didn’t have prior knowledge. Also when air travelers see and hear about a solution more often, credibility tends to go up.

Another misconception about sustainable travel that causes travelers to engage less is that people don’t understand what sustainable travel means. In a sustainable travel report by Booking.com, 40% of travelers said they don’t know how to travel more sustainably. Similarly, in our experiment with Hopper, 54% of participants felt the same. This indicates that travelers just don’t know how to make travel more sustainable and need to be educated on the topic.

The main takeaway here is that travel providers need to educate their customers and the world about possible options by bringing more transparency and background information on greener travel options into the travel-booking process. This includes offering a variety of options that allow reversing any negative effects people’s lifestyles may have on the climate. Furthermore, it’s important for travel providers to build trust and ensure credibility by working together with well-respected offsetting partners. USV’s Dani Grant correctly explains the doubts many people have today when engaging with offsetting schemes:

“As anyone who has tried to purchase offsets knows too well, buying offsets is wildly confusing: there are too many options that are hard to differentiate, it’s unclear how much carbon to offset, which project is most impactful, how much to pay for offsets, and how much of that payment is actually going to the offsetting project (in many cases, only 25% goes to the project and the rest goes to various middlemen). Plus, some offsets are fraudulent which leads to distrust across the whole industry.”

Wrapping it all up

The numbers are clear. Based on findings across various travel platforms, only around 1% of travelers actually choose to pay more in order to offset their carbon footprints generated from flying. So far, travelers aren’t walking the green talk.

However, not only the traveler is to blame for this. In fact, there are many ways travel providers can steer flyers towards greener behavior, including paying a premium. This can be done by integrating carbon offsetting options into the booking flow and providing a seamless, intuitive UI that places these options front and center instead of hiding them or offering them up as an afterthought.

Yet there’s a bigger question here. Should airlines and travel providers lean back and expect individual travelers to pay for their carbon emissions in the first place?

We believe many travelers don’t feel responsible for having to pay for greener travel, because they a) expect travel providers, e.g. airlines, to take on the responsibility of offsetting or reducing carbon emissions or b) expect their employers to pay for the impact caused by their business travel. The latter point is supported by data from TripActions, which found that “80% of business travelers claim to be concerned about the environment, however, 61% expect their employer to offset their business travels.”

Hopper is taking things in their own hands

Hopper agrees with this view and turned things around. Rather than solely placing the burden on the customers, they’re taking on the responsibility through their own carbon-offsetting program called Hopper Trees. For every hotel or flight booking made on the app, Hopper will plant up to four trees to offset the impact of their travel, at no extra cost to the customers. Users don’t have to opt in to be a part of this initiative.

The seamless integration of the Hopper Trees carbon-offsetting program into the user experience allows customers to feel better about both their travel and their environmental impact. Eco-conscious travelers who are aware of the program may very well choose to book their travel through Hopper rather than another provider that doesn’t have any carbon offsetting program in place.

Hopper’s example offers airlines and other travel providers a way to both promote more sustainable travel and attract customers interested in the topic (a majority of travelers as we have learned). With the increasing consumer concern surrounding carbon emissions, an integrated carbon offsetting program – or at the very least, a seamless booking flow that offers immediately visible sustainable options – is the way to go in the aviation industry.